SEMPORNA, Sabah: The coastal town of Semporna, on the northeastern tip of Sabah, has been dubbed the “gateway to scuba diving paradise” by local media. The islands near the town are blessed with white beaches and crystal-clear water. One of them is Sipadan, a world-famous and limited-access diving haven teeming with marine life.

But if the islands are paradise, Semporna itself could not be more different.

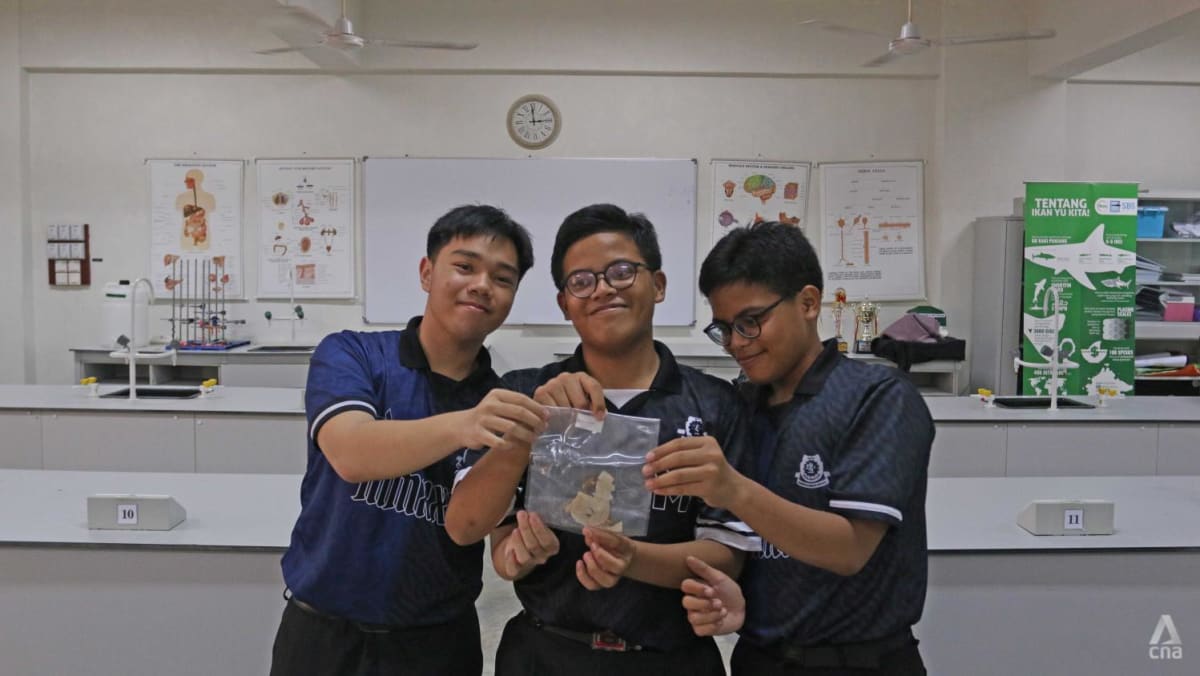

Not all hope is lost, however, if the ambitions of three 16-year-old students at a boarding school not far from Semporna were anything to go by.

Getting to the MARA Junior Science College involves turning off the main highway 20 minutes from Semporna. The bumpy road snakes through a small village before leading up to the campus, nestled between acres of oil palm plantations.

“Semporna is very dirty,” said Fahim Nazhan, a Form 3 student there. “The beaches on the mainland, the water was clear and now it’s turning brown. It’s becoming more polluted.”

Majlis Amanah Rakyat, or MARA, is a government agency that aids and trains Bumiputeras in the areas of business and industry.

Fauzi said he wants seaweed-based bioplastic to be “part of the solution”. “I hope this project can make this world a better place because we can see that plastic is a big problem for our country,” he added.

MAKING SEAWEED BIOPLASTIC

The group decided to start on their project as part of science class last year, armed with secondary school-level science knowledge and experience shared by their seniors.

“We chose seaweed because it is popular in this area,” Fauzi said, noting that they grew up eating seaweed, a dish found in every local eatery. “So, it is easy for us to find our raw material.”

Around the world, companies are also trying to use seaweed – one of the fastest-growing organisms on the planet – to make bioplastic. In 2013, UK start-up Skipping Rocks Lab introduced an edible water bottle made from brown seaweed.

The next and final step is the most critical: The solution is placed in a drying cabinet and heated at 60 degrees Celsius for 12 hours. Anything longer and the solution will burn up, creating a final product that is brown and crumbly.

Fahim, Fauzi and Fauzan have gone through this time-consuming process dozens of times over the past year, largely using trial and error. They have varied the amount of cornstarch and heating durations, trying to determine which combination produces the best result.

Fauzi described how they spent some nights in the science lab, straining to stay awake and ensuring their product does not overheat. Once, he fell asleep, only to be awakened by a burning smell.

“It is disappointing when this happens because the process takes so long and we have to wait for the results,” Fauzi said.

Rhodomaxx has managed to produce a small plastic bag from seaweed, and Chung said its tensile strength – or resistance to breaking – is “quite similar” to low-density polyethylene, the material used to make conventional plastic bags.

Its water resistance, however, is “nothing” compared to that of traditional plastic, so Chung has to find a niche market for his products.

For instance, his products will work with items that are shipped and transported in dry conditions or those that require water-soluble plastic packaging.

Another issue is pricing these products, as Chung highlighted that production costs were “quite high” and the final price “totally dependent” on economies of scale.

While the current plastic industry is supported by large petroleum companies, he said, bioplastic manufacturers do not have the same luxury.

Still, the fact that his company produces two types of seaweed products helps to reduce production costs.

In 2019, the Star reported that authorities in Semporna started an “all-out war” against litterbugs, on the orders of then-Sabah chief minister Shafie Apdal.

At least nine offenders were caught in a single day, and ordered to pay an RM500 (US$113) fine or do corrective clean-up work.

The latter option had a catch: They had to wear a vest with the word “monyet” (monkey) on it, in line with the council’s anti-litter theme that states only monkeys throw rubbish indiscriminately.

PRESSING AHEAD

Back at MARA Junior Science College, teacher Shahrul Hafiz Abdul Ghani, who mentors the seaweed project, said it is important not to just raise awareness about littering, but to also create alternatives to plastic.

Shahrul said he would oversee the project through his students’ five-year programme, noting that financially they are currently only supported by the school and sometimes his own money.

“If we can get another prototype, maybe in the future we can find an investor to invest in this project. I hope it can become a great product to sell and reduce the impact of pollution,” he said.